May 2022

The large earthquakes felt earlier this year were an unnecessary reminder of the need for alternative energy sources in Japan. Coupled with the Government’s move to shift away from Russian oil, renewable fuels such as offshore wind energy (OSW) have never looked more attractive. However, the developing Japanese OSW market, which has recently seen the entry of several big-name players, presents its own unique challenges.

OSW building momentum in Japan

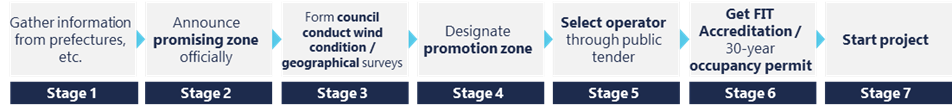

OSW development in Japan has made serious strides in recent years. In 2018, the precisely named Act on Promoting the Utilization of Sea Areas for the Development of Marine Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities established the legal framework for occupying outside port areas that have potential for OSW. The Act sets out the stages for the selection, designation and auction of areas for OSW projects (summarised below):

Significantly, 2021 saw the first winners of OSW auctions (Stage 5 above – the first stage when an OSW project can be said to have intrinsic value for a developer) announced: in June 2021, a consortium led by Toda Corporation won the first floating OSW auction (for Goto City, Nagasaki Prefecture); and in December 2021, consortia led by Mitsubishi Corporation – stunning their rivals and the wider market by offering unexpectedly low tariff rates – won all three of the first bottom-fixed OSW auctions (two in Akita Prefecture, one in Chiba Prefecture).

With a number of other areas already designated a “promotion zones” (Stage 4 above), and an ambitious 30-45 GW target of OSW output capacity by 2040 set by the Japanese Government, the OSW space will be an exciting one to watch in the years ahead.

Unique features of Japan’s OSW market

In our experience advising international clients on OSW deals, we have noticed the following somewhat distinctive features in the Japan market:

- Bottom-up selection process: Although Government Ministries (METI and MLIT), are principally responsible for the OSW selection process, our observation of market practice indicates that, since (i) support from a provincial government is necessary for a particular site to be properly considered; and (ii) developers’ apparent readiness toward the further progress of surveys / measurements and commitment to local stakeholders seems to be part of the selection criteria, the selection process is in reality more “bottom-up” than “top-down”. We have seen this manifested in the following actions typically taken by developers in Japan during Stage 1 or 2 above, or even prior – much sooner than is typical in some other jurisdictions:

- conducting meteorological surveys and other tests to gather useful information to submit to Government agencies who will make decisions as to which zones proceed to a further stage;

- seeking to build relationships with local stakeholders (see also below); and

- entering into an interconnection agreement to prove grid capacity for a particular site, even though this is not strictly required until later stages.

- International players need to be aware of eligibility criteria: Although eligibility criteria are specific to each OSW auction, past auction processes indicate show that although there are no restrictions on foreign ownership of an OSW project company, the project company itself must be incorporated in Japan. Further, past project guidelines indicate that only the experience and track record of the direct shareholder in the project company will be considered for purposes of the auction evaluation, except in exceptional circumstances (which have not been clarified). International operations should plan accordingly.

- Local stakeholder engagement and expertise is essential: In past OSW auctions, about one-third of the total “points” available for the qualitative component of the auction assessment (being 50% of the total assessment, with the other 50% of points coming from a reverse-price auction) are attributed to cooperation with local stakeholders and the knock-on effect to the local economy, but if anything, this understates the importance of these matters. In our experience, given the number of alternative areas vying to become “Promotion Zones” (Stage 4), significant opposition from local stakeholders can potentially end the prospects of a project completely. Developers will also need cooperation from Local Government bodies, fisheries cooperatives, or individuals owning strategically important land. For this and other reasons, overseas developers customarily seek local expertise, whether by acquiring, partnering with, or engaging domestic firms.

- The EIA process could be lengthy: Once a developer is selected as the operator of an OSW project by winning an auction (Stage 5 above), one of the key remaining hurdles to commencing construction and starting the project in earnest, is the environmental impact assessment process (EIA), pursuant to the Environmental Impact Assessment Act. This includes preparing an Environmental Impact Statement, describing the results of various surveys and assessments, which is examined by the prefectural governor and the public before it can be finalised. The EIA regime is not specific to renewable energy (its application extends to various projects / activities which have an impact on the environment), and there is limited market practice in terms of OSW-specific EIAs, but past examples indicate that this process could take 4-5 years or more – longer than many comparable overseas regimes. This is another reason why developers often start this process very early – i.e. Stage 1 / 2 or before – long before there is any certainty that the developer will be chosen in the auction.

The future is bright for Japan OSW, but new entrants to the market should be aware of the unique challenges to navigate, as well as the opportunities. Both regulation and market practice of the OSW selection process continues to change year-by-year, and we expect the market to continue to evolve in what will be a defining decade for renewable energy in Japan.

If you enjoyed this article, then our recent article on “Joint venture partnering on renewable energy projects” (here) may also be of interest

/Passle/5b6181bd2a1ea20b0498072f/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-25-14-08-22-737-699f0256b208a223bd0886c1.png)

/Passle/5b6181bd2a1ea20b0498072f/SearchServiceImages/2026-02-17-16-13-40-963-699493b4051add23620885dc.jpg)