As the end of 2020 draws nearer, so does the end of the Brexit transition period. The UK's Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has been increasing its staff levels significantly in preparation for its expanded workload, particularly due to an influx of European and global mergers that would previously have been subject to the European Commission’s exclusive jurisdiction under the 'one-stop-shop' principle, and which will now become assessable by the CMA. The CMA Chief Executive Andrea Coscelli recently stated that the CMA aspires 'very much to be at the top table discussing international mergers', and it has for some time now been deploying a number of tools in order to secure that seating arrangement.

In the last couple of years, the CMA has taken an increasingly assertive approach in merger control cases. This approach has generally yielded more conservative decisions. We examined the CMA’s data, comparing the two most recent complete financial years (FY18/19 and FY19/20) against the average of its outcomes in the four preceding financial years (from FY14/15 to FY17/18).

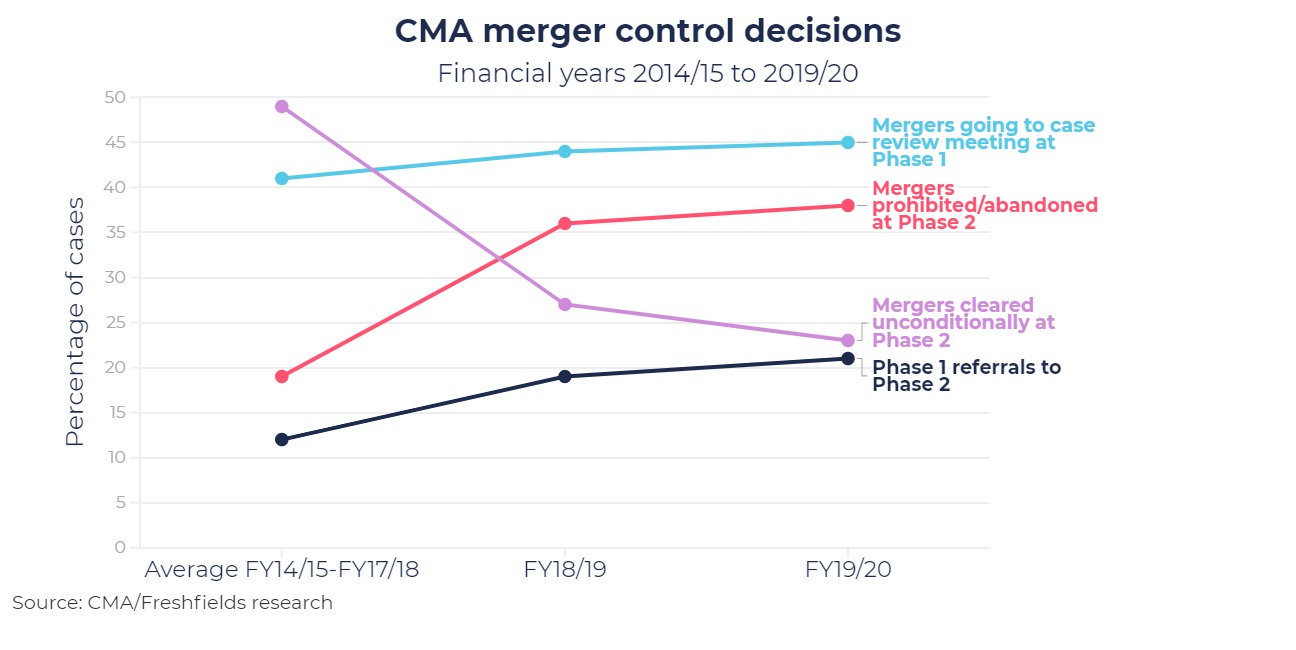

This reveals a clear trend towards more conservative merger control decisions:

- In Phase 1, the proportion of mergers referred to Phase 2 averaged 12 per cent of all those reviewed by the CMA, but has jumped to 19 per cent in FY18/19 and 21 per cent in FY19/20.

- The proportion of mergers going to a case review meeting at Phase 1 averaged 41 per cent, edging up to 44 per cent and 45 per cent in recent years. Although not a step-change, the CMA is analysing a great proportion of cases in more depth at Phase 1, with all the associated burdens this places on the merging parties.

- The most striking observation is that mergers prohibited or abandoned at Phase 2 previously averaged 19 per cent but the proportion has increased very substantially: to 36 per cent in FY18/19 and 38 per cent in FY19/20.

- Conversely, the proportion of mergers cleared unconditionally in Phase 2 has plummeted from a four-year average of 49 per cent to 27 per cent and 23 per cent most recently.

Along with these conservative decisions in merger control, we have also seen the CMA take a more aggressive stance on certain issues arising during merger investigations including: its own jurisdiction; initial enforcement orders; section 109 notices; and remedies.

Jurisdiction

While the UK has a voluntary merger control regime*, the CMA has wide discretion in determining whether it has jurisdiction to investigate a merger. It has used the flexible ‘share of supply test’ to claim jurisdiction, even in mergers involving one or more parties with a limited UK presence or nexus. The share of supply test allows the CMA to assert jurisdiction where the merging parties supply or acquire at least 25 per cent of any goods or services in the UK (or a substantial part of it), and where the transaction results in an increment to the share of supply or acquisition. The CMA can have regard to 'any reasonable description' of a set of goods or services and may have regard to value, cost, price, quantity, capacity, number of workers employed and any other criterion in determining whether the 25 per cent threshold is met.

Since 2018, the CMA has framed the supply/acquisition of goods or services narrowly to satisfy the 25 per cent threshold (and assert jurisdiction) in a number of cases, including:

- Sabre/Farelogix – based on the supply of services facilitating indirect distribution of airline content to just one UK customer (British Airways). The CMA also considered the threshold satisfied in the supply of services facilitating the indirect distribution of airline content to UK travel agents with respect to bookings for certain specific non-UK flights/travel destinations (eg Kazakhstan, Sweden and Puerto Rico).

- Roche/Spark Therapeutics – based on the number of UK-based employees engaged in 'activities' relating to the relevant overlapping treatment products for Haemophilia A and, separately, the number of UK patents procured in relation to treating Haemophilia A.

- Mastercard/Nets – based on the number of suppliers participating in a tender, with the CMA considering that only five to eight tender participants were credible suppliers and the merging parties were two of them. This merger was ultimately referred to the European Commission, but the CMA set out in its referral request why it considered that it had jurisdiction nonetheless.

The CMA’s flexible approach to taking jurisdiction is currently being challenged by way of a review before the Competition Appeal Tribunal (CAT) of its use of the share of supply test in the Sabre/Farelogix decision. Notwithstanding this, as demonstrated by the consultation on its revised merger guidance, the CMA is seeking to double down on its broad interpretation of the share of supply test in order to take jurisdiction over deals that it believes should be subject to CMA scrutiny. Given that guidance does not have the status of law, the decision of the CAT in the Sabre/Farelogix decision will be an important clarification of the outer edges of the CMA’s powers.

Initial enforcement orders (IEOs)

The CMA can issue an IEO, typically after closing, requiring the merging parties to keep their businesses separate and independent, pending the end of the CMA’s investigation. IEOs are highly disruptive to merging companies as they apply to the whole business, including subsidiaries, parts located overseas and parts of the business that do not overlap with the target’s business. Derogations can be requested to allow for certain activities to occur, but these are not guaranteed, can take days or weeks to be approved and can be subject to significant safeguards.

An IEO will almost always be issued in a merger investigation relating to a completed merger, but the CMA is issuing them with greater frequency in relation to anticipated mergers as well. Nine IEOs have been issued in the last three years in relation to anticipated mergers. This approach means that even before completion, the parties may be limited in their activities and subject to greater monitoring by the CMA.

The CMA has the power to fine parties up to 5 per cent of aggregate worldwide turnover for breach of an IEO and it has used its power to impose a number of large fines since 2018 including:

- PayPal – fined £250,000 for inadvertently contacting potential UK customers as part of a cross-selling pilot campaign intended to target customers in France and Germany.

- Nicholls (Fuel Oils) Limited – fined £146,000 for relocating the target’s staff to its premises, using a Nicholls-branded mini tanker and driver to deliver to the target’s customers and providing compliance statements late.

- Vanilla Group Limited – fined £120,000 for selling assets (washing machines) used in the target’s business.

- Electro Rent Corp – fined £300,000 for serving a break notice to terminate the lease over its only UK premises, and for appointing its CFO as a director of the target.

- Ausurus Group, EMR Limited – fined £300,000 for using its bank accounts when dealing with the target’s customers and suppliers, and failing to give the target’s managing director a clear delegation of authority.

Section 109 notices

The CMA frequently uses section 109 notices to compel parties to provide written responses to questions and copies of internal documents during its merger investigations. Section 109 notices can also be used to compel senior management to be interviewed by the CMA. We expect that these powers will be used more often going forward. The CMA has included in its draft revised merger guidelines specific reference to its powers to conduct interviews (and to compel participation) as a more formal process than an ordinary information-gathering call.

The CMA’s former Chairman, Lord Tyrie, has described the CMA’s information-gathering and compliance powers as 'manifestly inadequate'. Lord Tyrie argued recently in the House of Lords that the CMA requires additional powers to allow it to gather information from a wider range of sources including digital information – such as machine learning, cloud data and algorithms – which are not easily captured by existing legislation.

The maximum penalty for failing to comply with a section 109 notice is £30,000. The CMA has issued a number of significant penalties in the last three years:

- Amazon was fined £55,000 in 2020 for failing to provide certain documents in a timely manner. The total sum comprised a £25,000 fine and a second (maximum) £30,000 for breaches relating to three section 109 notices.

- Sabre Corporation was fined £20,000 in 2019 for the late production of documents, which had been part of a pool of documents that had been mistakenly marked as privileged and initially withheld.

- Rentokil Initial was fined £27,000 in 2019 for failing to provide responsive documents including strategy documents.

- AL-KO Kober was fined £15,000 in 2019 for producing responsive documents late despite the delay being due to innocent and non-deliberate human errors.

- Hungryhouse was fined £20,000 in 2017 for failing to identify and provide key responsive documents because of deficient search and review processes.

In 2019 the CMA suggested that the section 109 penalty powers should change so that the maximum penalty is based on a proportion of turnover, as is the case with an IEO breach. If such an amendment passes, we can expect to see significantly higher penalties for failing to comply with section 109 notices.

Remedies

When divestment remedies have been offered by the parties in Phase 1, the CMA has insisted on an upfront buyer requirement in at least 50 per cent of cases. An upfront buyer requirement means that the CMA will not accept the undertakings in lieu unless a sale agreement (typically conditional only on acceptance of the UILs by the CMA) has been concluded and the buyer has been approved by the CMA, following public consultation. Even if an upfront buyer is not required, the CMA may require other significant safeguards before accepting divestment undertakings in lieu (eg that if the divestment cannot be completed in the specified period, a trustee will be appointed to complete the divestment at no minimum price).

Remedies have also become more common at Phase 2, with remedies being required in 38 per cent of cases in FY19/20, up from the 36 per cent in FY18/19 and higher than the average 32 per cent over the preceding four‑year period.

After the end of the Brexit transition period…

The CMA’s data show increasingly conservative decisions and these examples demonstrate an ever more assertive stance on issues arising during merger investigations. The revised CMA mergers guidance currently undergoing consultation (on jurisdiction and procedure, the mergers intelligence function and substantive assessment) is further evidence of a CMA seeking to define its mandate very broadly and to allow it to play a leading role in global mergers. As the CMA’s jurisdiction expands after the end of the Brexit transition period, we can expect the CMA to continue to use all of the tools at its disposal in merger control investigations to ensure that it remains high on the agenda of business.

* Although the debate is likely to continue post Brexit as to whether the UK should move to a mandatory and suspensory regime.

/Passle/5b6181bd2a1ea20b0498072f/MediaLibrary/Images/2024-12-04-16-24-21-724-67508235376ff9ba249f2b08.jpg)