'Regulatory reform' – we’ve heard this phrase countless times from his predecessors, to the point where it sounds more like catchy propaganda than a meaningful promise. By now, it’s hard for most of the Japanese population to believe that it's actually going to happen. But since his inauguration this September, it seems Prime Minister Suga has already made some moves towards change.

Having been 'requested' by PM Suga, major mobile carriers such as NTT Docomo, KDDI and Softbank, which currently dominate Japan’s expensive (relative to many European and Asian countries) telecom market, agreed to reduce mobile phone charges. Concurrently, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (parent company of NTT Docomo) launched a public takeover to take private NTT Docomo, which, at a cost of approximately US$38bn, will be one of the largest such transactions of all time.

It is speculated that this take-private is driven by the pressure to reduce mobile phone charges, although the conglomerate has asserted the purpose is to enhance NTT Docomo’s competitiveness. Separately, the Suga administration has disapplied an antimonopoly rule to a merger between long-time-slumping regional banks, and also started discussions to urge a business restructuring of small to medium companies. Could this time be different?

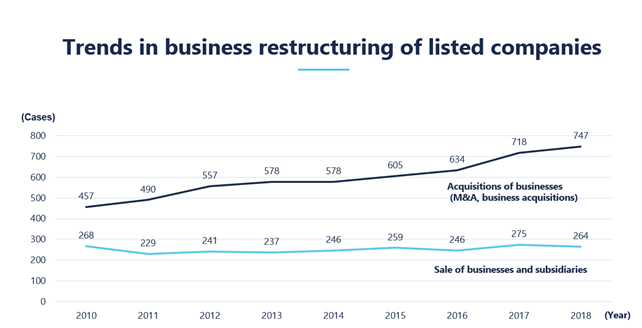

Push for corporate restructures

Source: the METI’s guidelines.

It’s true some Japanese conglomerates/large companies already started 'de-conglomeratisation'. We have seen earlier this year Japanese luxury toilet maker Lixil Group’s disposal of household goods retailer Lixil Viva and Takeda Pharmaceutical’s disposal of its consumer health products business to Blackstone.

Coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic and the Japanese government’s nudge, now is a time of opportunity to change for Japan Inc. It will give corporate management a good excuse (yes, unfortunately they need one) to carve out non-core businesses which they can justify both internally (to its employees) and externally (eg to their 'OB' alumni).

Meanwhile private equity firms appear bullish on Japan and waiting for their opportunities to use their dry powder. Japan’s (over ¥160tn) Government Pension Investment Fund’s appointment of 'gatekeepers' and fund of funds managers for its PE mandates will further fuel the growing momentum.

An increase in carve-outs?

With these market dynamics changing, all seems to be set for a boom in Japanese carve-outs. But what is a carve out in Japan? Is it as mysterious as the Japanese culture and language? The short answer is 'not really', but with some local peculiarities to take note of, like many other jurisdictions.

There are two typical carve out structures - an asset purchase (jigyou joto) and an absorption-demerger (kyuushuu bunkatsu).

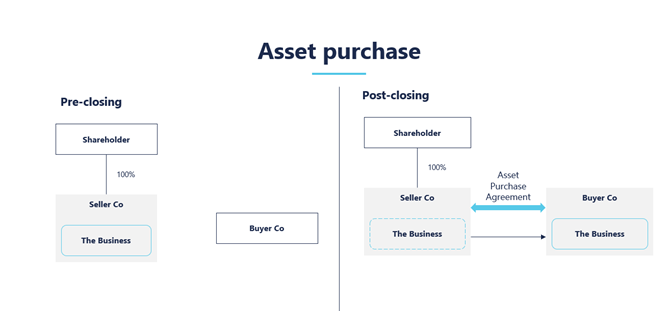

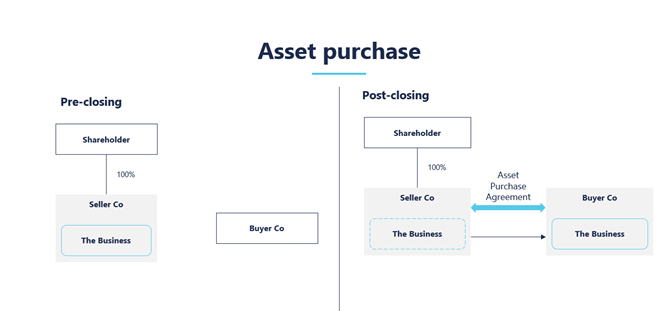

1. Asset purchase method

The asset purchase method is very simple: a seller transfers the target business directly to a buyer.

2. Absorption demerger method

Another typical carve-out structure is a demerger. A seller sets up a new Japanese corporation ('NewCo'), and then transfers the target business by an absorption-type demerger (kyushu bunkatsu) under Japanese law. Then the seller will transfer the shares of NewCo to the buyer. The seller’s tax and accounting analysis will generally determine who the shareholder of NewCo should be – either the seller or the seller's shareholder.

It is also possible for a buyer to take over the business directly from the seller by way of a demerger without establishing NewCo, but this is usually not a popular choice because of the additional administrative burdens and necessity to operate the business from day one.

Which structure is more favourable to a buyer? Tax is usually a significant factor in this. Legally, it really depends on deal speed, the size of carve-out businesses, and other factors, but generally speaking, as a buyer you should ask yourself:

- Do you wish to 'cherry pick' the target’s employees? An asset transfer gives you more flexibly (but please note, there is not complete freedom due to court precedents). If there is a risk of unwanted employees transferring, consider seeking protection against this;

- Do you wish to apply new employment contracts (eg buyer’s group employment terms/pension and benefit scheme) to the transferring employees, or you are fine with existing employment contracts (including pension-related labilities) automatically transferring to you? Again, an asset transfer gives more flexibility. These employee aspects are key factors for a buyer in choosing a carve out structure (aside from tax). This is because changing or terminating an employment contract post-transaction is not easy, if not impossible, due to infamously strict Japan labor laws;

- How quickly you need to implement a transaction (a demerger will take at least one and half months due to the required statutory process, whereas an asset transfer can be done theoretically within a day in many cases); and

- How many consents are required from employees/customers/supplies to transfer assets and contracts to a the buyer entity/NewCo and how difficult these will be to obtain (in some cases an asset transfer could pose more risks of employee departures/business dilution).

It is likely to be a bumpy road forward given the fallout from COVID-19 on Japan’s economy, but as more and more financial data becomes available for 'COVID-affected' reporting periods, and Prime Minister Suga’s reform plans crystalise and develop, we will hopefully see corporates gain sufficient confidence to conduct carve-outs, such that these transactions become a much more common (and positive) feature of Japan’s M&A landscape.

/Passle/5b6181bd2a1ea20b0498072f/MediaLibrary/Images/2024-08-09-14-06-51-922-66b6227b9a6577f0bc97991a.jpg)

/Passle/5b6181bd2a1ea20b0498072f/MediaLibrary/Images/636d0c50f636e91ee467aac0/2023-03-28-19-33-54-219-64234122f636e91be89dd86a.jpg)